J.P. Morgan’s Efforts to Shield Itself From European Market Fallout Prompted Disastrous Bets

J.P. Morgan’s Efforts to Shield Itself From European Market Fallout Prompted Disastrous Bets

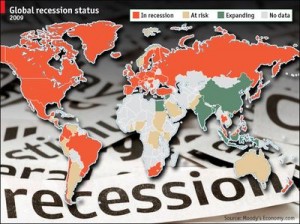

J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. told traders several months ago to make bets aimed at shielding the bank from the market fallout of Europe’s deepening mess. But instead of shrinking the risk, their complicated bets backfired into losses of as much as $200 million a day in late April and early May, people familiar with the situation said.

Regulators in the U.S. and U.K. are examining what went wrong, who is responsible and whether J.P. Morgan should have told investors about the losses sooner, according to people familiar with the matter.

While attention has focused on large positions taken by a trader nicknamed “the London whale,” he and other traders were carrying out instructions from a bank executive, these people said.

The instructions were to find a way to reduce the bank’s exposure to positions in the credit markets that had grown too large. But some of the trades they made didn’t work, culminating in the company’s announcement Thursday of more than $2 billion in losses.

The trading losses reverberated Friday, as J.P. Morgan shares fell 9.3%, or $3.78, to $36.96 in New York Stock Exchange composite trading at 4 p.m., erasing $14.4 billion in stock-market value. It was the biggest decline since August, and trading volume soared to its highest level since at least 1984, according to FactSet Research Systems. The stock fall subtracted nearly 30 points from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which fell 34.44 points to 12820.60.

After the end of regular trading, Fitch Ratings cut its credit rating on J.P. Morgan to A-plus from double A-minus. The rating firm cited “potential reputational risk and risk governance issues.” Standard & Poor’s said it might downgrade the bank.

J.P. Morgan declined to comment Friday. “We should not let this detract from what we are here for—to serve our customers,” Chairman and Chief Executive James Dimon wrote in a memo sent to the bank’s 270,000 employees on Thursday evening. On Friday, some workers in the sprawling bank’s consumer operations told each other they were baffled by the complex missteps that occurred in the firm’s Chief Investment Office.

Some executives said privately Friday that a cleanup will have to include holding people accountable. According to people familiar with the matter, attention is focused on Ina Drew, J.P. Morgan’s investment chief, who reports to Mr. Dimon. Ms. Drew, who earned $15.5 million last year, is the executive who instructed traders to reduce the bank’s risk.

Through a bank spokesman, Ms. Drew, Mr. Macris and Mr. Iksil declined to comment.

Ms. Drew’s office manages the bank’s money with the goals of gaining a return above J.P. Morgan’s cost of capital and of hedging some of the bank’s exposures. It is housed inside the bank’s corporate unit, one of seven business segments within J.P. Morgan Chase.

As bank officials sought in recent weeks to identify the scope of the problems in her business, Ms. Drew tried to play down the issues, said one London-based executive.

The trading losses—$2.3 billion, according to a person close to the bank—accumulated over just 15 days in late April and early May, or an average of $153 million a day. The chief investment office managed a securities portfolio worth about $374 billion.

Behind the losses: unusual movements in the relationships between various derivative indexes focused on investment-grade and junk-bond corporate debt, both in the U.S. and Europe, according to someone close to the matter. The moves may have been due in part to hedge funds taking the other side of J.P. Morgan’s trades.

There were smaller losses during the first quarter that alarmed some within J.P. Morgan, but executives were reassured when measures of risk settled back down. The executives would later discover that those measurements were flawed.

After The Wall Street Journal reported April 5 on the large positions being taken by Mr. Iksil, top executives, including Mr. Dimon, participated in a review of trading positions. They knew there might be losses market movements but were satisfied about the strategy, said people close to the bank.

But the week after the bank’s April 13 first-quarter earnings call, concern mounted when losses started to balloon to as much as $200 million a day. Several teams were assigned to review the positions, and they discovered the trading mistakes. These ranged from errors in how the bank hedged an existing hedge to how it offset the size of an existing trade that served to protect the bank, said people familiar with the situation.

To employees in London, where J.P. Morgan’s businesses are spread across at least three buildings, signs of trouble surfaced at the start of May. J.P. Morgan Chief Risk Officer John Hogan and investment bank head Jes Staley arrived from the U.S. and started twice-a-day meetings. Joining them was Daniel Pinto, who is in charge of Europe for J.P. Morgan’s investment bank.

In New York, the board met several times in the past few weeks to discuss the snafu and how to deal with it. There were no discussions about removing Mr. Dimon as CEO, said a person familiar with the discussions, but the events raised new questions within the bank about why better controls weren’t in place.

One trader estimated more than a dozen hedge funds and banks profited by taking the other side of J.P. Morgan’s trades. Firms such as BlueMountain Capital Management LLC and BlueCrest Capital Management LP each scored gains of about $30 million, according to people familiar with the matter. The firms declined to comment.

Regulatory inquiries into the bets include a review by the Securities and Exchange Commission, according to a person familiar with the matter. The informal inquiry is focused on whether the loss was disclosed to investors at a sufficiently early stage.There are no firm guidelines on when projected trading losses become “material” to investors and therefore need to be disclosed.

Some lawmakers said Friday the trading blowup reinforced the need for tougher financial regulations, with some of the fiercest criticism aimed at Mr. Dimon. He has been one of the loudest foes of certain rules imposed since the financial crisis.

“J.P. Morgan Chase, entirely without any help from the government, has lost, in this one set of transactions, five times the amount they claim financial regulation is costing them,” said Rep. Barney Frank (D., Mass.), former chairman of the House Financial Services Committee and a co-sponsor of the Dodd-Frank financial-overhaul law of 2010.